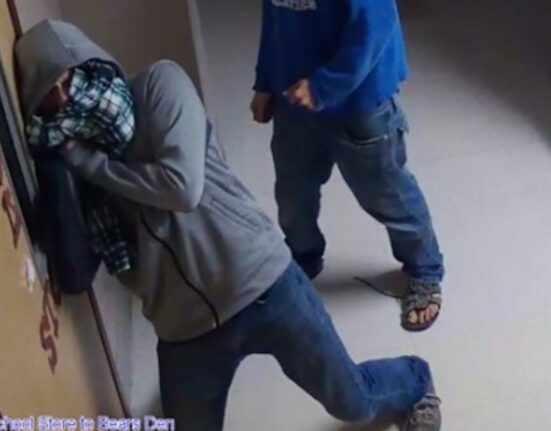

When the once tight-knit relationship between ex-bikie enforcer Jonny “Two Guns” Walker and CFMEU bosses crumbled, betrayal hung heavy in the air. Walker, a convicted criminal and former Banditos bikie Sergeant at Arms, felt abandoned by union leaders who had once welcomed gangland figures like him with open arms.

As investigative journalist Nick McKenzie delved into the unraveling of the CFMEU’s bikie enforcer scheme, Walker found himself at odds with those he once considered allies. In a revealing sit-down with McKenzie, Walker didn’t hold back in expressing his feelings of disloyalty and deception. He even went as far as calling McKenzie a “dog,

” showcasing the depth of his frustration.

The fallout exposed a rift between the ex-union bosses, like John Setka, who appeared more concerned about their own survival than standing by men like Walker. Setka’s ostentatious display of getting a bikie-style tattoo after leaving his position only added salt to the wound for Walker. Reflecting on Setka’s actions, Walker remarked, “I would say he’s try-hard… It’s like leaving a biker club and getting a tattoo on the next day.”

Walker lamented how these former union leaders turned their backs on individuals who were placed in influential roles within the construction industry projects by the CFMEU. Despite their past involvements in criminal activities, including violent incidents within bikie clubs, Walker believed they deserved support and recognition for their contributions to unionism and workplace safety.

In defense of his position as a union delegate despite his checkered past, Walker emphasized that his expertise as a tradesman and dedication to upholding safety standards made him an ideal candidate for such roles. He highlighted his commitment to reform and family responsibilities while challenging perceptions surrounding his suitability due to his criminal history.

Although labeled as intimidating due to his boxing background and unflinching demeanor, colleagues on construction sites where he worked attested to Walker’s professionalism and non-threatening behavior towards coworkers. Despite past associations with notorious bikie gangs like Bandidos, Rebels, Mongols, and Hells Angels being brought into question during public scrutiny, Walker stood firm on defending their capability to hold employers accountable and protect workers’ rights.

While some may view the influx of ex-gangland figures into union positions skeptically, believing it was orchestrated for power plays rather than genuine representation of workers’ interests; others see them as assertive individuals capable of challenging unjust practices within the industry. In contrast to critics pointing fingers at corrupt practices within unions involving bikies’ appointments, there are voices acknowledging systemic flaws needing rectification beyond mere blame games.

As Australia grapples with industrial reforms amid ongoing investigations into organized crime links within sectors like construction – characterized by unsolved firebombings shedding light on deep-rooted issues – efforts are underway to rebuild transparent governance structures free from corruption influences. The narrative surrounding CFMEU’s tainted legacy underscores broader concerns about prioritizing personal agendas over collective welfare.

Despite diverging opinions on whether ex-bikies should serve as delegates or not within unions given their controversial backgrounds; there is consensus that restoring trust in institutions demands accountability and transparency from all stakeholders involved. As Australia navigates through this turbulent period shaped by conflicting loyalties and power struggles in its labor landscape; one thing remains clear – rebuilding trust requires integrity above all else.

In this evolving narrative blending personal grievances with institutional shortcomings lies a crucial lesson for organizations aiming to regain public confidence: solidarity must triumph over self-interests if true reform is to take root successfully amidst adversity.

Leave feedback about this